Häagen-Dazs

April 29th – May 26th, 2022

Haägen-Dazs is a show of new work by Rasmus Røhling composed, in his own words, through a kind of “lasagna logic.” Meaning is piled upon meaning in a “syntax of stupidity” whereby everything becomes more, rather than less, complicated. The following is laid out in layers to honor this method, and to guide the visitor through some of the exhibit’s reference points:

I.

In the late 1950s, without any hint of derivativeness of conceptual art still yet to come, the American co-founder of Haägen-Dazs, Reuben Mattus, sat at his kitchen table babbling strange syllables over and over until he created a unique, Danish-sounding proper noun for his iced cream company. Denmark was selected for its excellent reputation for dairy products as well as its exemplary treatment of the Jews during WWII. The name is thus the result of the founder’s private performance, which embodies his feelings about the country, his impression of its language, as well as all that the brand name has since come to signify.

II.

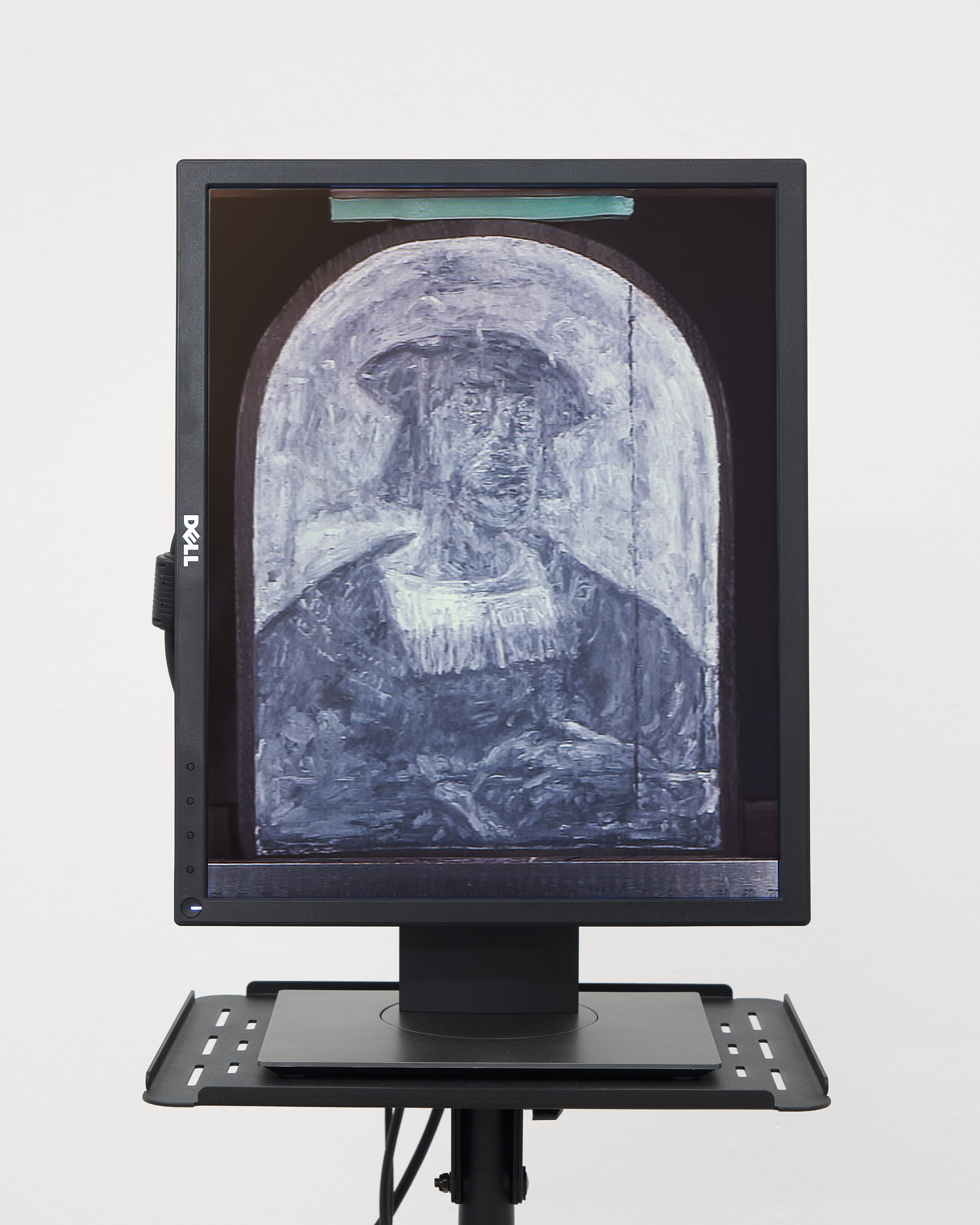

King Christian the Second ruled Denmark from 1513–23. In 1514, painter Michel Sittow was called to Copenhagen to produce a very small but powerful portrait of the new king. Today it resides in the collection of the Statens Museum for Kunst. Researchers recently used X-Ray technology to examine the regal painting, whereby they found a completed portrait of an entirely different sitter in golden fleece living underneath that of Christian II. The best guess is that the man below is Charles the Fifth, a Hapsburg relative (by marriage), deduced from his rather long chin.

III.

In Sittow’s day, paintings such as this portrait of Christian II were part of the visual economy of power. Today, scientific technology has overtaken the role of the artist as supreme imagemaker. The MRI scanner, paradoxically, is a powerful tool that can produce a 3D rendering of the insides of a human body that slides through it like a hot dog yet it itself cannot be photographed. While it is on, the magnets will destroy a camera, producing what the artist calls a “black hole of representation.” Hospitals, by contrast, are full of reproductions of artworks, particularly Impressionist and Post- Impressionist painting. The trauma of one’s procedure can thus fix itself in one’s psyche to a serene landscape by Monet or Seurat.

IV.

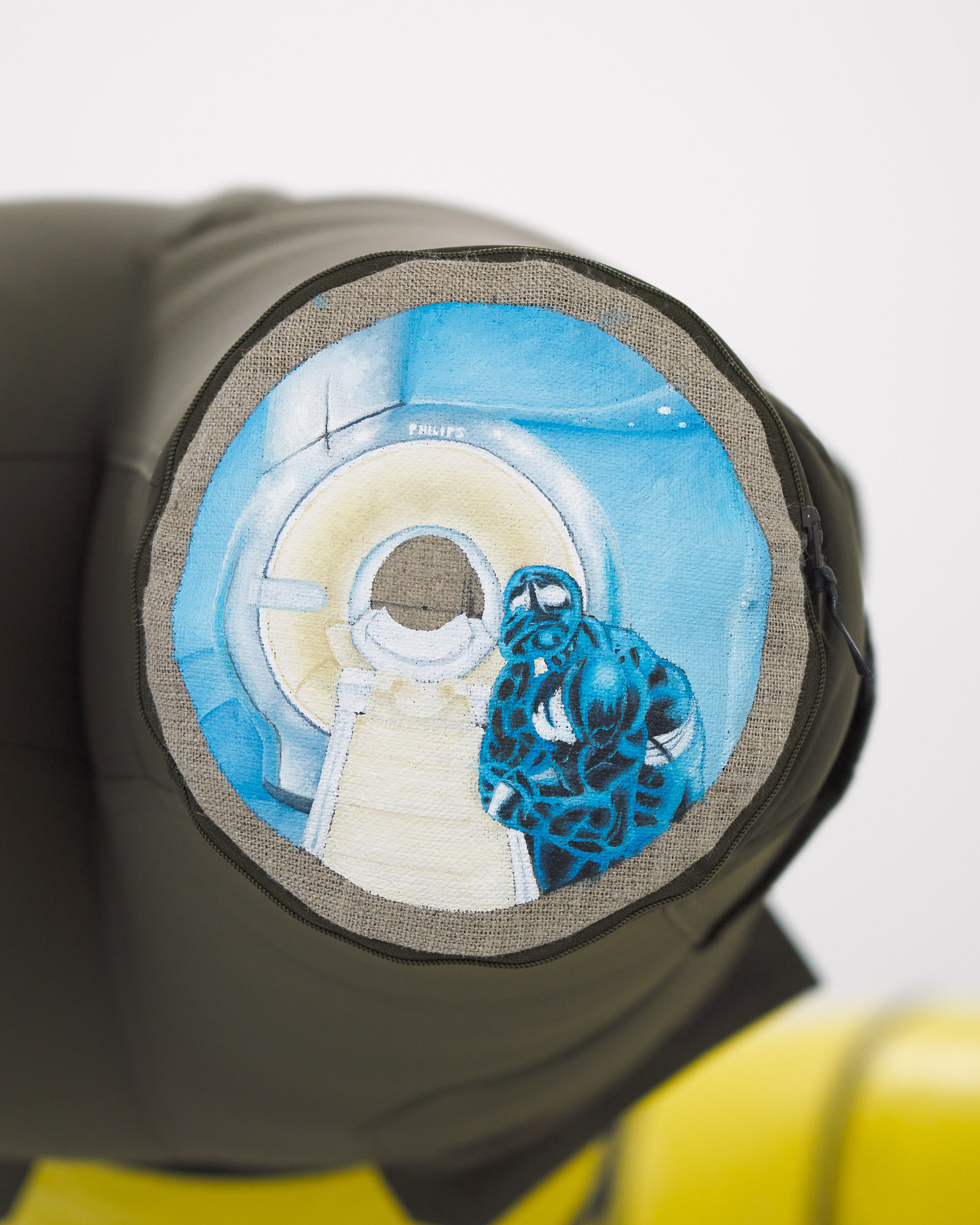

Moods or temperaments since the time of Hippocrates were associated with the body’s humors: melancholy, meaning black bile, was the depressive result of its excess. In 1514, Dürer etched a famous representation of the artist as melancholic. In a diptych painting zipped onto the legs of Colombia trekking pants, Venom, a virus from outer space manifested as a character in the Marvel universe is cast as Melancholia (or the depressed artist). In the second “panel”, a still-life style cornucopia made out of a Hövding airbag-style bike helmet displays a wealth of fresh fruits grown in different regions of the world. Written in Latin on the surface below are the words “welfare stateprolapse” (approximate translation). The diptych is animated by a ventilator used to circulate the air in field hospitals and creates a kind of charmed snake sculpture (calling to mind the medical emblem of the Rod of Asclepius) bearing two distinct paintings at each of its ends. Like the airbag helmet, the field hospital is a form that pops up in times of war or other crises.

Amy Zion

Rasmus Røhling. Häagen-Dazs. April – May, 2022. Photo by Brian Kure

Rasmus Røhling. Häagen-Dazs. April – May, 2022. Photo by Brian Kure

Rasmus Røhling. Häagen-Dazs. April – May, 2022. Photo by Brian Kure

Rasmus Røhling. Lazaret (diptych), 2022. Utility ventilator, flexible PVC duct, zip-off hiking pants, steel, oil on canvas (Ø17 cm each). Dimensions vary with installation

Rasmus Røhling. Lazaret (diptych), 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Lazaret (diptych), 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Lazaret (diptych), 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Lazaret (diptych), 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Lazaret (diptych), 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Lazaret (diptych), 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Live X-ray feed of Michel Sittow’s portrait of King Christian II, painted in 1515, currently in the collection of Statens Museum for Kunst,2022. DV video on loop 23min. mixed media. Dimensions vary with installation

Rasmus Røhling. Live X-ray feed of Michel Sittow’s portrait of King Christian II, painted in 1515, currently in the collection of Statens Museum for Kunst, 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Live X-ray feed of Michel Sittow’s portrait of King Christian II, painted in 1515, currently in the collection of Statens Museum for Kunst, 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Live X-ray feed of Michel Sittow’s portrait of King Christian II, painted in 1515, currently in the collection of Statens Museum for Kunst, 2022. (Detail)

Rasmus Røhling. Live X-ray feed of Michel Sittow’s portrait of King Christian II, painted in 1515, currently in the collection of Statens Museum for Kunst, 2022. (Detail)